Warlord Games

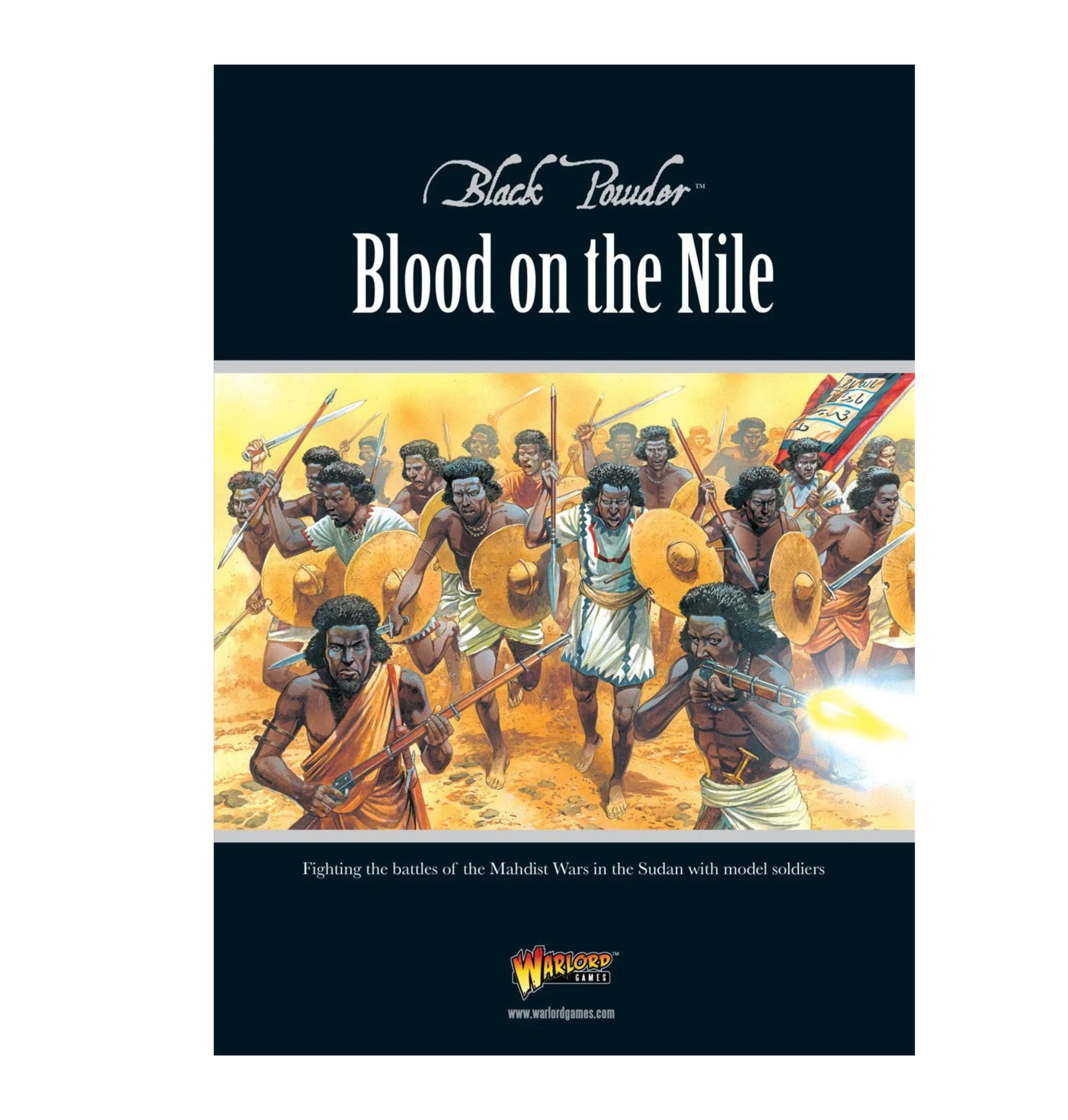

Black Powder Blood of the Nile

Couldn't load pickup availability

Disclaimer: This is not a physical product. You will receive a digital download of your eBook after your purchase.

The year was 1884, forty-seven years since Queen Victoria ascended to the throne of the world’s greatest empire on which the sun would never set. Eight years earlier, she became Empress of India having led her small island onto the global stage while the rest of the world danced to the British tune.

India was the jewel in the crown, but the hard-working, industrious types that proliferated in Victoria’s empire dominated from Australia to Canada and persuaded the locals how beneficial all this was for them. Of course, empire building was not easy: the Americans didn’t want anything to do with it, and French noses were all put out of joint over one thing or another. Then there were some natives who wouldn’t do as they were told and stood in the way of progress until properly civilized. But by 1884, most of the world knew who was in charge and the rest didn’t dare to take up their cudgels against the British.

Compare all that to the Egyptians. Thousands of years before they had an empire of their own and built the pyramids and things so the world wouldn’t forget about it. Then others came and the Egyptian Empire disappeared into the sand. Until 1819 that is, when the ruler of Egypt, the Khedive, wanted a taste of Empire and took charge of the Sudan – the large seemingly empty space on the map to the south of Egypt. The Egyptians made a complete hash of running the Sudan, however, and rebellion was only a matter of time.

In 1881, a mystic came out of the Sudanese desert claiming he was the Mahdi, a new

Mohammedan prophet. The Egyptians sent a token force to arrest him only to have it

sent packing, as happened with every attempt afterwards. The following year, in an

unconnected episode, the Egyptians thought they could do without European meddling in their affairs. Sir Garnet Wolseley and a few thousand of Britain’s finest soldiers sorted that situation out quickly enough, and Britain had no choice but to offer advice to the Khedive from a much closer distance, so she moved in her civil servants to show him how to run things properly. That left the thorny problem of the Mahdist rebellion unsolved, but the British had little time or money to waste on such trivial matters and expected the Egyptians to take care of it.

The Egyptians continued to flounder in the Sudan. Even when British officers took command of Egyptian troops to give them some backbone, those that the Mahdi’s men didn’t kill or convert still ran away. Now you can’t have British officers being defeated; it is bad for morale and upsets the politicians. And it displeased Her Majesty, and that would not do. Wolseley was itching for another fight, but Prime Minister Gladstone, that rather reluctant imperialist, wasn’t for it. He sent ‘Chinese’ Gordon to Khartoum instead, which just about anyone could have told the Prime Minister was adding fuel to the fire. Gordon soon found himself surrounded in the Sudanese capital and none of the fellows doing the surrounding cared much for Gordon’s brand of religion any more than he cared for theirs. Gladstone finally got the message and let Wolseley off the leash. In the meantime, British soldiers got down to business along the Red Sea ports to halt the Mahdist progress in that region. Once again the wheels of Victoria’s Empire were in motion with only the Mahdi’s fanatics standing in the way.

Share